further: feature

So, I’m driving down Broadway in my hometown of Boulder, Colorado. Ahead of me are two Subarus, pacing each other like they’re in love … so no passing is happening.

Even better, they’re both going at least 10 miles-an-hour under the speed limit. This is an all too common scenario in Boulder, and it drives me crazy.

Soon, I’m yelling choice expletives at the two drivers (not that they can hear me). My blood pressure is soaring, and my agitation level is off the charts as I helplessly crawl behind the oblivious citizens ahead of me.

The primary cause of my distress is:

-

A. Subaru owners in general.

B. The recreational marijuana these drivers are likely impaired by.

C. Myself.

While I could make cogent arguments for both A and B (and I often do), the correct answer is C. When it comes down to it, I have no one else to blame for my reaction other than myself.

Let’s look at this realistically. At worst, I’ll arrive at my destination a minute later than otherwise. And yet, the fit I’m throwing is completely out of proportion to that slight inconvenience.

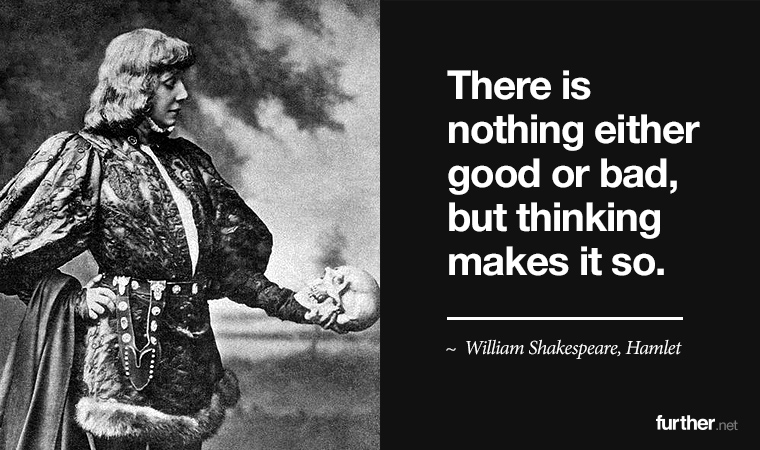

This experience is “bad” not because of the tiny delay, but because of my beliefs about incompetent (and possibly stoned) drivers, among other things. It’s a fairly complicated amalgamation of judgments that is “making” me upset.

But ultimately, it’s all “me” that’s at the root of the distress. That’s the fundamental basis of the philosophy of Stoicism, which dates back originally to Zeno in Greece, and later adopted by Epictetus, Seneca, and Marcus Aurelius in Rome.

First of all, let’s ignore the modern connotation of the word stoic, which tends to reflect a weary, uncomplaining resignation in the face of suffering. Stoicism is really about accepting circumstances as they are, taking appropriate action, and achieving tranquility of mind in the process of getting things done.

Author Oliver Burkeman sums it up this way:

-

“The only things we can truly control, the Stoics argue, are our judgments – what we believe – about our circumstances. For the Stoics, then, our judgments about the world are all that we can control, but also all that we need to control in order to be happy; tranquility results from replacing our irrational judgments with rational ones.”

This is not to say that negative emotions resulting from things beyond our control aren’t real, but rather that our response to these emotions is the source of the level of distress we experience. Poverty, harm to a loved one, and even thoughts of our own death are not positive experiences by any means — and yet our mindset ultimately determines the mental impact of these and other challenging life situations.

In case you think this is just some dusty old philosophical noise, it’s also the basis of modern psychological treatment. The roots of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) can be traced back to Stoic thinking, and it’s how scores of people have overcome life trauma, addiction, and other afflictions.

In essence, Stoicism is about letting go of our attachment to thoughts about outcomes we can’t control (ranging from death to traffic), and focusing on our reactions to the thoughts themselves, which we can control. The first step, as always, is to become aware of your irrational reactions as they’re happening, and eventually, before they happen.

You’ve been conditioned your entire life to make judgments about what’s good and bad, desirable and undesirable. Ironically, the way to live a happier, more effective life is to unlearn your conceptions of what should be, and deal effectively with what is.

- Why Stoicism is one of the best mind-hacks ever

- The Antidote: Happiness for People Who Can’t Stand Positive Thinking

- The Obstacle is the Way: The Ancient Art of Turning Adversity to Advantage

Think of it this way: meditation is about (among other benefits) realizing that your thoughts, beliefs, and conditioning are intangible and separate from what you really are. Stoicism is a life strategy for implementing and living with the truth of that realization.

As always, simple … but not easy.

further: health

Is Protein as Important as We Think?

Laboratory research on caloric restriction has shown remarkable longevity gains in mice by radically cutting the amount of food consumed. The latest findings add a twist, however … it’s not that you have to starve yourself overall, it’s that you need to cut way down on protein.

This is counterintuitive because we constantly hear that high protein, low carb diets are better for us (at least in a weight loss context). Physician Garth Davis has a book coming out this fall called Proteinaholic: How Our Obsession with Meat Is Killing Us and What We Can Do About It that aims to take down the protein myth. In the meantime, here’s some food for thought:

- Long life: Balancing protein and carb intake may work as well as calorie restriction

- Our Misplaced Obsession With Protein

further: wealth

From the “Fixing the Wrong Problem” Department

“It’s like if someone was punching you in the face and their idea for how you might feel better about that situation is for you to learn to take a punch better, rather than they stop punching you in the face.”

further: wisdom

Lean In to Your Fear

Being afraid of losing your job is more distressing than actually losing your job. Most are more afraid of public speaking than death. People are willing to pay more for the absence of fear than for happiness.

If all that sounds irrational, it gets worse. We’re afraid when we feel like we’re not in control, even though in reality we’re rarely truly in control of anything other than our actions and reactions.

If you’re noticing a theme here with today’s feature, you’re on to something. Make sure to note the Stoic technique of negative visualization:

__________

It’s time for me to stoically return to my real job. But that’s okay, because when you share Further with a friend, it’s all good:

Thanks as always! Until next week …

Keep going-